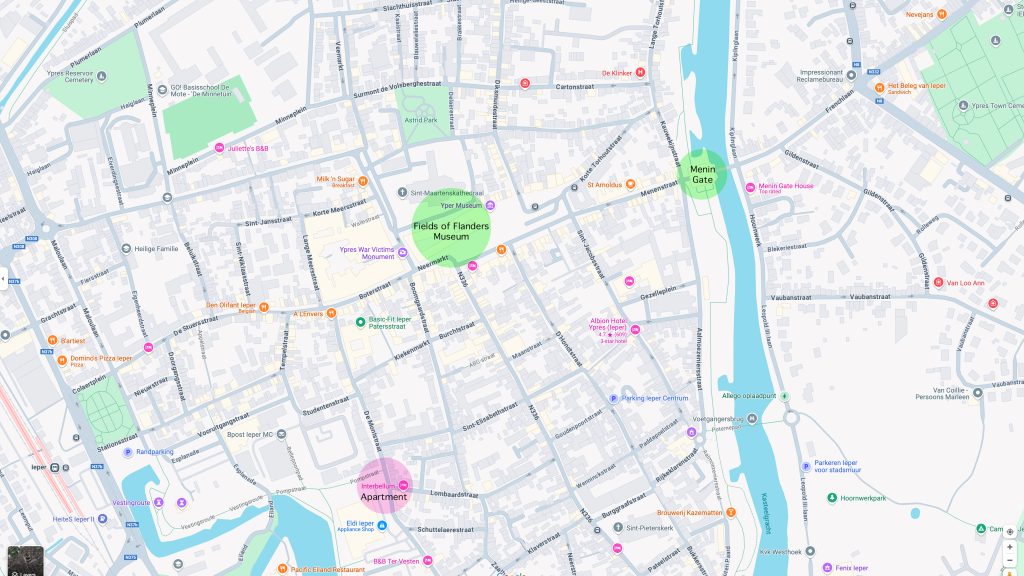

October 2024 Cas and I travelled to Lippstadt for Herbstwoche but they had asked if we could visit some WW1 sites on our way. After some research, I booked an apartment in Ypres.

Ypres, in Flanders was close enough to Calais and Dunkirk to get to without too much of a drive and I found a couple of cemeteries where Bending’s were buried.

The Trench of Death is alongside the Yser Canal not far from Diksmuide. You can read more about the site on Wikipedia.

We didn’t walk the entire length as it was wet under foot in places, but explored the bunker complex which, along with the photos on the information boards gives a good impression of what life – and death – was like for the four years the area was fought over.

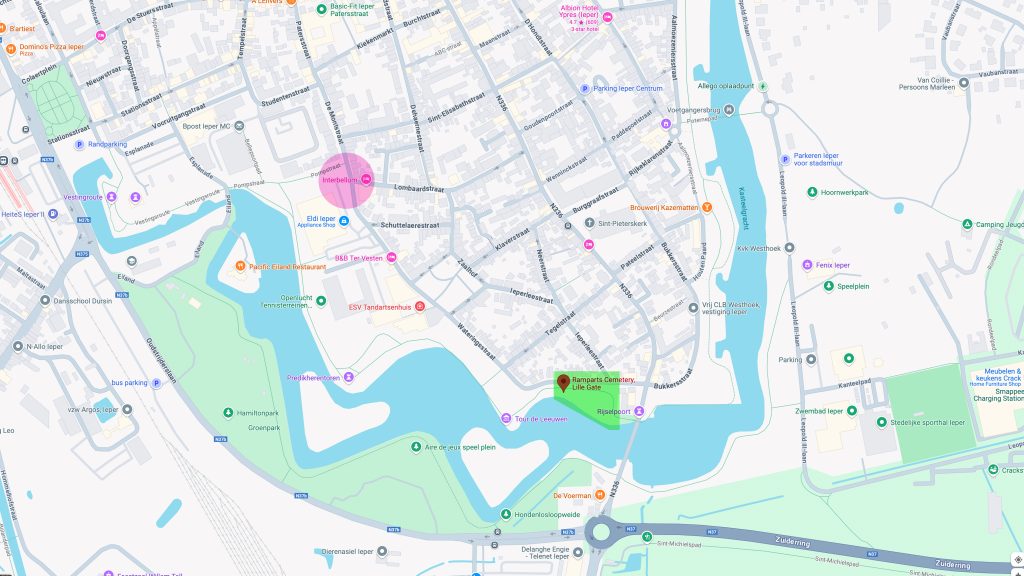

After our visit we drove on to Ypres and met up with our host so he could give us the keys to the apartment – ‘Interbellum’ which I had booked through Booking.com, and show us around, before leaving us to unpack. The two bedroom ground floor flat was close enough to walk into the town square where there was a collection of restaurants.

Along the way, we spotted some keys fixed to the pavement. A local resident explained they are memorial keys to residents of Ypres that were killed during the conflict. They are grouped together roughly in the area where they died.

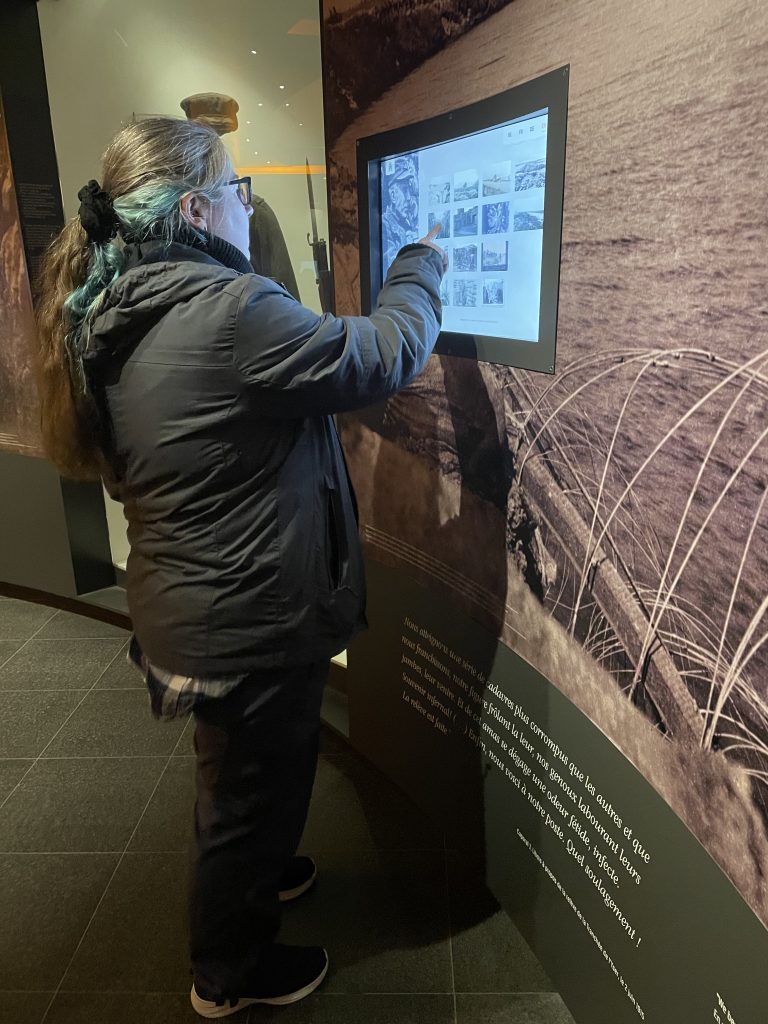

The Cloth Hall in Ypres now houses the ‘In Fields Flanders’ Museum. The exhibits occupy the second floor and there is a wealth of information (lots of reading) telling the story of the Ypres Salient. To take it all in takes some effort – both Cas and I could have done with a coffee break half-way around, but there’s also a feeling this is a bit of a pilgrimage and that dictates the mood within.

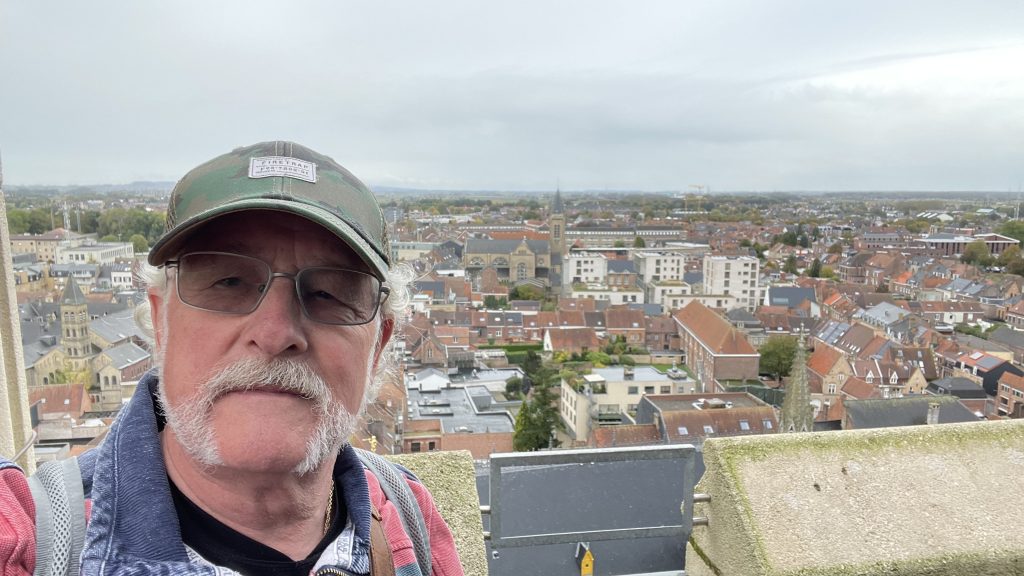

I chose to pay a little extra and add a climb up the belfry tower for views over the rebuilt town. With nearly 300 steps, most of which are in a narrow spiral stone staircase, it takes a bit of effort and I had to rest a couple of times but once up there, the views are the reward.

It’s worth remembering that Ypres was just a pile of rubble at the end of WW1, with virtually every building destroyed. It’s nice to see that it wasn’t just the town’s landmarks that were rebuilt to mimic the originals, but many of the residential houses too.

After the Museum, we found somewhere for lunch then walked to the Ramparts Cemetery to visit the grave of one F J Bending, a Lance Corporal of the Royal Army Medical Corps who was killed on 15th March 1915, aged 21.

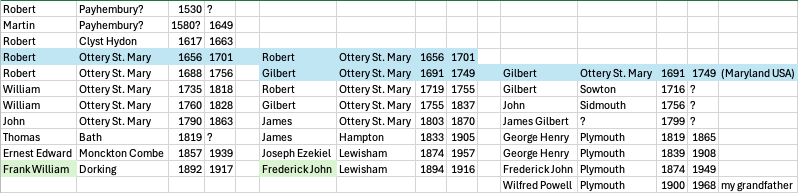

After checking the ‘John Bending’ website to see, I found that both Bendings we found share common ancestry with me with their ancestors also stemming from the Devon (Ottery St. Mary) Bendings.

My ancestors go back to a Robert Bending of Payhembury in Devon, because of the reformation under Henry VIII, records were lost, so this is as far back as can be defined, though there’s evidence that goes back to the Norman Conquest of 1066. The common ancestor to all three – Frank William, Frederick John and me – is Robert (1656-1701) of Ottery St. Mary. He had (at least) two sons; Robert and Gilbert. The brothers are ancestors to all three of us. Gilbert was sentenced to death in 1720 for theft of some silver spoons, but he was repreived and instead sent to work as a slave in Maryland, America. After 13 years Gilbert became a free man and married again, even though he was still maried to his wife back in England, but I guess to her, he was dead, though she didn’t remarry and outlived Gilbert.

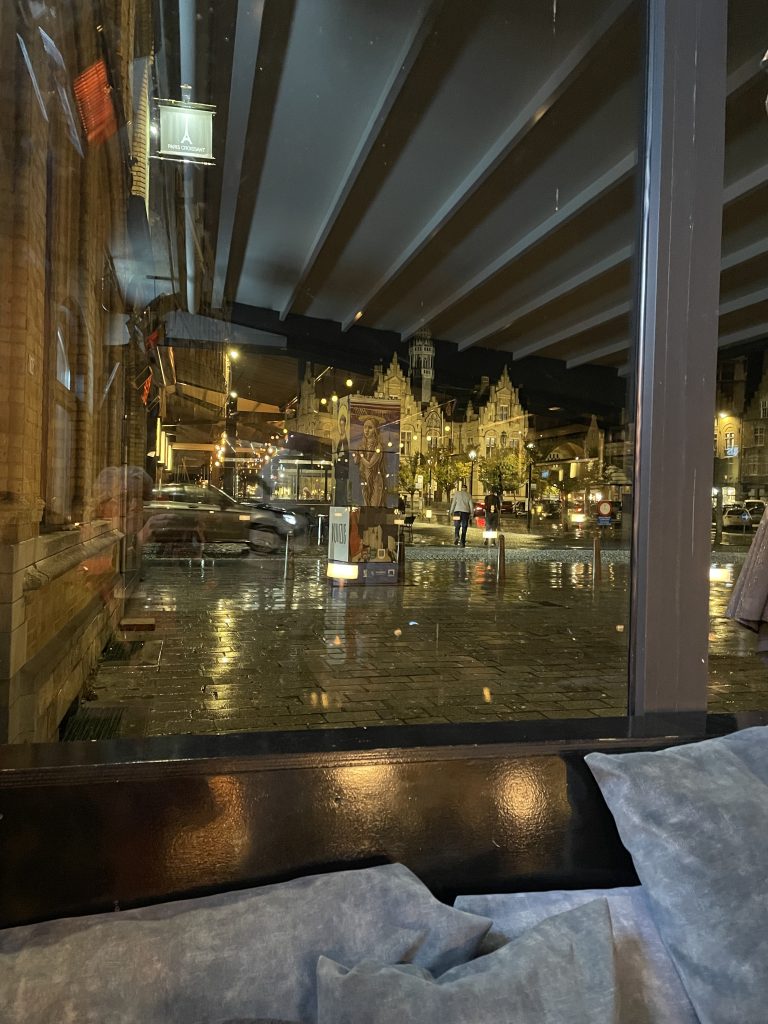

After a break back at the flat, we rested weary legs before heading back to the main square to find a bar before having some food. The restaurants and bars around the main square are, as expected, very much geared for tourists, but we managed to find a small bar just off the square where the locals were enjoying some refreshments. Bonus was some track cycling on the wall-mounted TV.

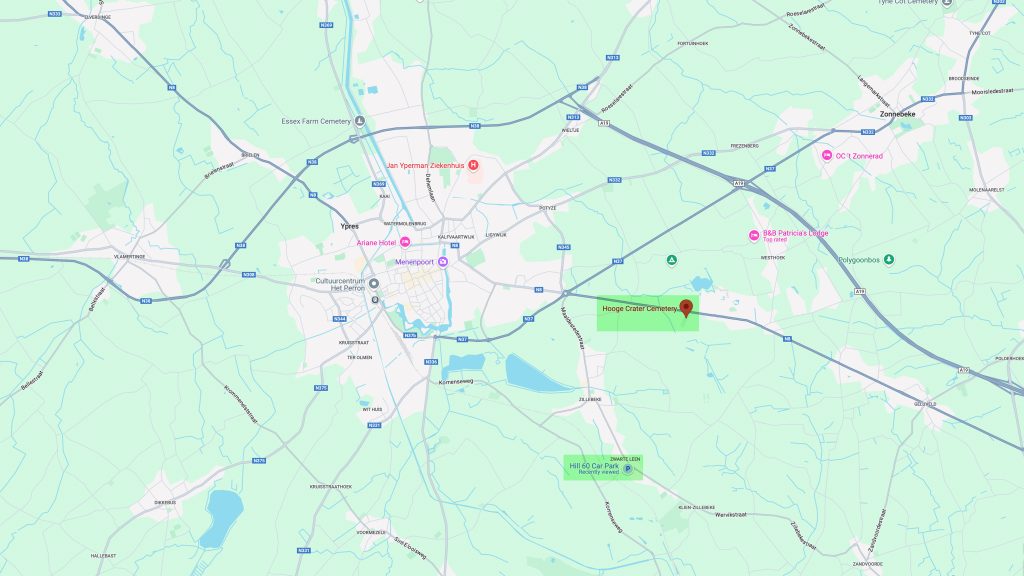

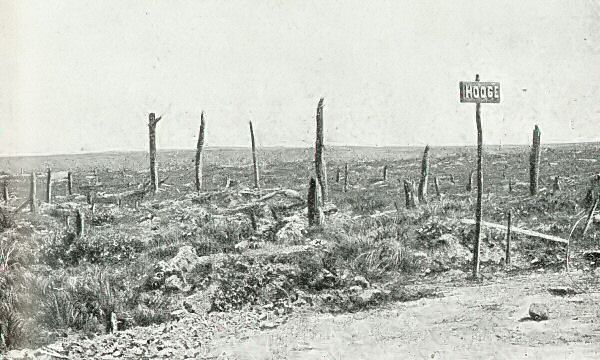

Next day we drove the short way out to the Hooge Crater, but my research was lacking, as once there, we found it was closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Still, aside from the main crater, there are four smaller ones that now form a pond within the grounds of a hotel just a little way from the Museum. This is open to the public to wander. Entry is unmanned with an honesty box for the €2 fee.

A German built block house. At the other side of the pond is a British built one. This whole area changed hands several times throughout the war, with both sides exploding underground mines.

Having wandered the site we headed back to the car for a short drive to the car park at Hill 60.

From the car park, a wooden walkway takes you across the crater of Hill 60 and over the uneven remains of overgrown trenches and shell holes. At a couple of points the German and British lines are marked, only 30 yards apart.

Hill 60 was next to a railway cutting and there’s a small green with memorials right next to the present-day bridge over the rail line.

On the opposite side of the tracks to Hill 60 was another rise known as the Caterpillar – largley made up from the spoil of the railway cutting. On 7 June 1917, at 3.10 in the morning, two tunnel mines were detonated underneath the German positions at Hill 60. The 204 Division lost 687 men that day. The Caterpillar Crater is huge, nearly 80 metres in diameter and 16 metres deep.

Next morning we were due to leave for Lippstadt, but that evening there was one last thing I wanted to do before leaving Ypres. We walked in to town for food but stayed off the alcohol as I wanted to go to the Menin Gate to pay my respects at the ‘Last Post’ which takes place at 8:00pm every evening.

Over 54,000 names of British and Commonwealth soldiers appear on the walls of the gate, but just in the Ypres Salient, the total losses, including French, Belgian and German casualties number around a quarter of a million.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old.

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.